Quakerism is intimately connected to, and arose from, the politics and experience of Seventeenth-Century England. It was founded by an amazing young man named George Fox. Fox (1624-91) lived during a period of Civil War and religious intolerance. The Church of England and the Puritans were at each other’s throats and, through this period of regal beheadings and secular violence, Fox quietly sought his Light.

Raised in a Calvinist tradition, Fox spent four troubled years in his late teens and early twenties, confused by the political upheaval and religious orthodoxy of the world that surrounded him. He was skeptical of the ministers who sought to guide (and, at times, condemn) the devout, but he was unclear as to the alternative. Then, in an epiphanal moment, he found it:

“As I had forsaken the priests so I left the separate preachers also, and those esteemed the most experienced people; for I saw there was none among them that could speak to my condition. When all my hopes in them and in all men were gone, so that I had nothing outwardly to help me, nor could I tell what to do, then, I heard a voice which said, ‘There is one, even Christ Jesus, that can speak to thy condition’; and when I heard it, my heart did leap for joy. Then the Lord let me see why there was none upon the earth that could speak to my condition, namely, that I might give him all the glory. … And this I knew experimentally [i.e., experientially].”

Charged thus with the Spirit, and clearly possessed of tremendous gifts of persuasion, Fox enthusiastically developed his experiential insight of the Inward Christ, and his conviction that there is “that of God in every person.” Fox and his followers preached a gospel of primitive Christianity, citing chapter 15 of the Gospel of John: “I have called you friends; for all things that I have heard of my Father I have made known unto you.” Fox referred to his followers as “Friends of Jesus,” or “Friends of the Truth.” Thus was coined the “Religious Society of Friends.”

From Fox’s spiritual insight there developed beliefs that came to be known as “testimonies,” shared as a common heritage and the foundation for Quaker faith and practice even to today.

First, there is the principle of the Light Within, or immediacy. Fox believed that each person bears that of God, and that there was no authority for any intermediary between a person and God. No one is more capable of experiencing divine Light than any other person, and each person is equally fallible. God is knowable by — and, indeed, within — each person, and the experience of immediate connection to God is discernible corporately. Each of us is able to communicate with the Divine at any moment, directly and immediately, in the midst of a worshiping community. Thus, to Fox, the center of the true “church” was the human soul and the gathered experience of the worshiping community. He despised (and preached against) “steeple-houses” and what he considered to be ostentatious displays of religious ritual. Worship, taught Fox, occurred when open and yielded hearts are assembled in silent community to wait upon God. Plain and simple gathering places became the meeting rooms and worship-places of sincere and simple friends, waiting together in silent, expectant worship, undistracted by graven images or ecclesiastic trappings, and free from the leadership and preaching of what Fox called “hireling” ministers. The principle of immediacy is at the core of Quaker testimony, and leads by extension to all other aspects of Quaker faith and practice.

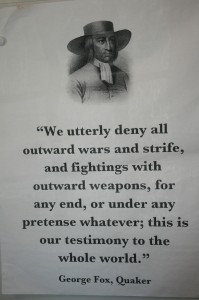

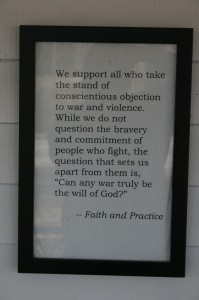

Second, the principle of pacifism. Fox believed that there was no principled resolution to the conflict between the teachings of Christ and the practice of violence. In 1661, the Religious Society of Friends penned one of its enduring testimonies in its Declaration to Charles II:

Third, the connected principles of equality and simplicity. Fox made no political distinction between men and women, or between young and old. As Friends worship God together, waiting in a silence charged with an almost mystic expression of faith, each member of that group possesses a unique portion of the Inward Light. Thus, by simple extension, Fox taught that Quakers should not humble themselves, or pay tithes, or doff their hats to others, on the ground that no man should be held so as to humble others. God alone is to be submitted to. Nor, to Fox, was it faithful for Friends to wear colorful clothes, or to adorn their bodies (which is to say, their private churches) with ostentation. Friends’ language, too, should be simple, humble, plain, direct and truthful. Quakers still avoid swearing oaths — even in court — on the ground that truthful speaking is to be expected at all times, on or off a witness stand, and to acknowledge the need for oath-taking is to admit a duality in one’s integrity. For centuries Quakers kept to “plain” speech, forsaking the use of “you” and “your” (reserved for society’s elite in the Seventeenth Century) in favor of the simple “thee” and “thy.” Plainness and candor continue to mark Quaker vernacular. To this day, many a Quaker feels honored to be the recipient of the solidly-delivered: “I thank thee, Friend.”

One could plainly forecast the political and social predicament, in mid-Seventeenth Century England, of a group of highly individualistic people who refused to join the army, refused to pay taxes, refused to conform to the procedures of courts of law, and aggressively proselytized against the established state church and its leaders: the priests, the bishops and the King himself. Quite understandably, Quakers were regarded as traitors, and subjected to imprisonment and forfeiture of property. George Fox, when he was not languishing in cruel imprisonment, traveled to Scotland and the New World to spread his teachings. His words found fertile reception in America, where (thanks to William Penn and other early British/American Quakers) the Religious Society of Friends came into its own. Among the most influential American Quakers of the late Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Centuries was David Sands, of Cornwall. His story is the first chapter of the history of Cornwall Friends.